Brutality in Burma has been occurring for decades.

A friend recently spent time in the country and has published this powerful story in the New York Times about the fledging democracy movement there:

U Win Tin, Myanmar’s longest-serving political prisoner, was tormented, tortured and beaten by his captors in the notorious Insein Prison for nearly two decades. Now, at 80, he faces a new kind of torment: watching colleagues from his political party decide whether to play by the rules of the junta that put him behind bars.

Released in September 2008 after more than 19 years in prison, Mr. Win Tin remains remarkably spry, upbeat, and politically engaged. A co-founder of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy, he is a vocal opponent of taking part in national elections set for next year. The vote, along with the implementation of a new constitution, would introduce a shared civilian and military government after four and a half decades of military rule.

But while the constitution, passed in a disputed referendum held amid the widespread devastation of Cyclone Nargis in 2008, allows elected representation, it accords special powers to the military in what the junta calls “disciplined democracy.” Many critics call it a sham.

“The election can mean nothing as long as it activates the 2008 constitution, which is very undemocratic,” Mr. Win Tin said in a recent interview.

…

Mr. Win Tin — warm, razor-sharp and clearly determined — said the junta might have released him, shortly before his jail sentence was complete, in order to split the party. He admitted that “we are having some arguments about whether we are going to participate in the elections or not,” but insisted that there was “no conflict within the party now.”

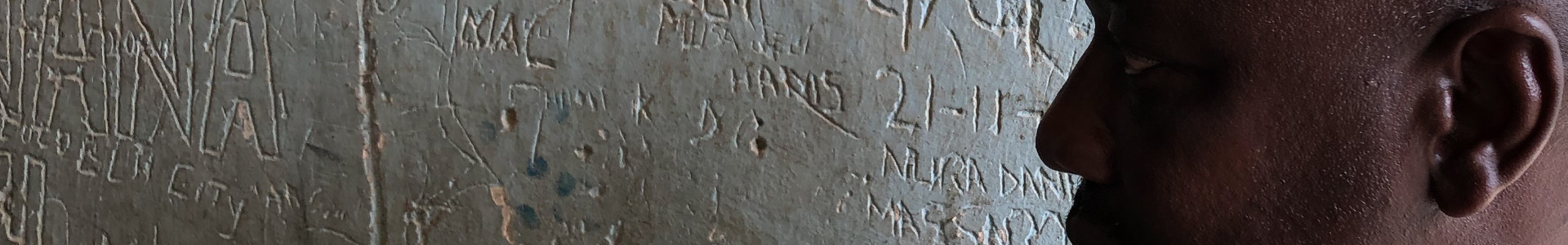

Before being jailed for three years in 1989 after he became secretary of the then newly formed National League for Democracy, Mr. Win Tin had worked as a journalist. In 1991, he was given 10 more years for his involvement in popular uprisings in 1988 that were crushed by the military. In 1996, he was given seven more years for sending the United Nations a petition about abuses in Myanmar prisons. Much of the time, he was in solitary confinement.

“I could not bow down to them,” he said. “No, I could not do it. I wrote poems to keep myself from going crazy. I did mathematics with chalk on the floor.”

He added: “From time to time, they ask you to sign a statement that you are not going to do politics and that you will abide by the law and so on and so forth. I refused.”

When all his upper teeth were bashed out, he was 61. The guards refused to let him get dentures for eight years, leaving him to gum his food.

Early this month, Mr. Win Tin was briefly detained after he wrote an op-ed that appeared in The Washington Post, criticizing the ruling military junta and its plans for the election next year.

“I think they are trying to intimidate me, to stop me from appearing in the foreign media,” he said.